When senior Acting BFA Trinity Ross chose to direct famed Black playwright Dominique Morisseau’s Blood at the Root for the final show of Crimson Stage’s fall 2022 season, it was not because it was the first of Morisseau’s plays to be put on a UA theatre stage. Last year, one of the department productions, just across the building in the Allen Bales Theatre, was Morisseau’s Pipeline. Both plays address the inner workings of Black characters who have to navigate primarily white public school environments; while Pipeline focused on a young man’s struggle to find his identity in a private school system separated from his inner-city background, Blood at the Root focused on students at a high school in rural Louisiana and the different challenges that context presents.

As Trinity stood in front of the last audience of Blood at the Root, she reminded the crowd that her directing work for this production is just one part of many of Crimson Stage’s student-led efforts. Each aspect of this student theatre organization, from its directing, arts management, and technical efforts is student-led. Over the school year, the organization gives the opportunity for any student on campus to showcase their theatrical talents. Unlike department shows which are chosen and directed by faculty and staff, Crimson Stage shows are a direct reflection of the issues and messages students want to project onto a stage. Often Crimson Stage’s show season is a blend of student written and licensed play material.

The title for Blood at the Root comes hauntingly from lyrics to Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” in which

Southern trees bear strange fruit. Blood on the leaves and blood at the root. Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze.

Morisseau used Holiday’s words to help center the show around the real-life events of the Jena 6 case. In 2009, six black teenagers were convicted for the assault of local white student Justin Barker after a number of racially charged events surrounding school “traditions” escalated, including nooses hung from a tree. Blood at the Root dramatized their interactions with the systemic discrimination present at their rural Louisiana high school.

The main visual point of the show was the oak tree, “Old Devoted,” in the school yard. The main character of the show, Raylynn, played by senior Musical Theatre major Jayln Crosby, explained in the opening scene that only a select group of white upper middle-class cliques can sit under the shade of the tree. Other students on the grounds had to stay out in the hot sun. While the oak tree still stands tall on the real Jena High School campus, the “Old Devoted” depicted in Blood at the Root was portrayed by the play’s ensemble throughout the show; at both the beginning and end of the performance, all of the cast members gathered around a platform center stage and raised the arms as branches of the old oak tree.

One of the most impactful of these moments in the show featured only one of the cast members as the oak tree. After main character Raylynn took a stand against the discriminatory tradition of only white students sitting under the tree and decided to sit under the tree herself, unnamed students hung nooses on the branches of the tree in retaliation. As a rest, the ensemble walked out for their afternoon break in the schoolyard where, on the platform, stood Raylynn’s brother De’Andre, played by junior BFA Chris Watts. The lights dimmed as red scarfves hung from his outstretched arms. When Raylynn ripped each of the scarves off De’Andre, the air was sucked out of the room. Suddenly, the stakes of the play were raised as it became clear that those nooses meant more than just the hateful act of teenage bigots. They represented a racially discriminatory system that is deeply rooted within our justice and education systems.

In addition to these powerful non-verbal moments, many scenes in Blood at the Root that relied on spoken word poetry in addition to the dialogue. In the author’s note of the script, Morisseau urges artists to “let it flow,” inviting the performers to find intention from rhythm, speed, and delivery. Every performer delivered their lines with so much anticipation for the next that it felt like I was rushing right along with them. Each pick-up of the next character’s line carried the same weight and intention. The beat was never dropped. This cast had such a deep connection to each other’s work that the lines flowed with an infectious rhythm.

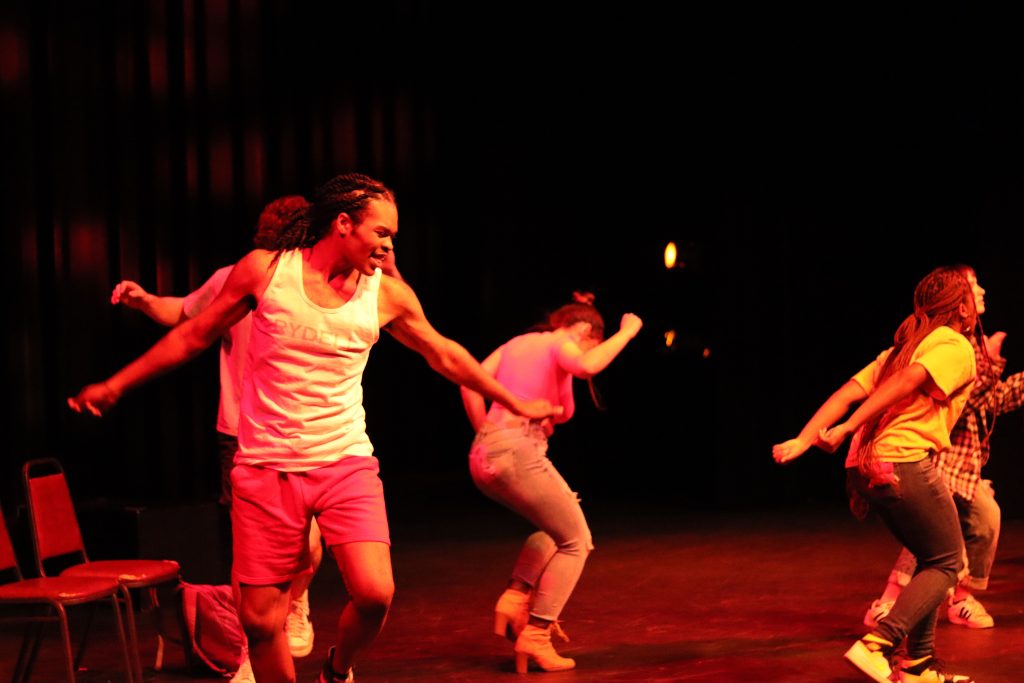

My favorite part of this play was a scene entitled the “Telephone Game,” which anticipated an altercation between Colin, De’Andre, and the five other Black students. The entire ensemble strode across the stage in all different directions. Each of them blurted out rumors of how the fight started. The stage turned into an organized chaos of he-said-she-saids until Colin and De’Andre were standing center-stage facing each other. Scenes like these rely on trust of your fellow performers. Everyone has to bring their best energy to the table, or else the rhythm falters. The clear choreography of this scene worked alongside the cacophony to suggest how school gossip can run rampant, especially when it is related to violence. The reactions of the students revealed where each of them stood on the racially charged issues occurring in the school.

Lest this moment be taken for granted, pre-production promotion videos shared demonstrated the detailed work that went into cultivating these kinds of powerful movements. It is typical practice to have a student from the Crimson Stage executive board enter the rehearsal space during tech week to capture some of the behind-the-scenes work of performers in their student-run productions. In a video on Crimson Stage’s Instagram (@crimsonstage), they captured Blood at the Root’s warm up process. Trinity put on a song to which the ensemble made a large circle in the rehearsal space, and each of the cast members found their own rhythm as they were encouraged to enter the middle of the circle. Not only did this process allow for the performers to dive into their improvisational skills, but each time a new cast member entered the middle of the room, it was the ensemble’s job to hype-up their energy. No matter who was in the middle, every person in the room was expected to maintain the energy. When watching the show, the results of this process resonated on stage.

This production of Blood at the Root not only tackled Morisseau’s serious, timely text regarding justice and the double standards of racism in a small rural community, but also made her words visceral. Each monologue was deeply rooted in an authenticity to the text and a connection to the larger ensemble. Shows like these always leave me grappling with my own reflections on the environments that I grew up in and the systems of power that are still perpetuated in the rural South. Something that I have appreciated out of this department has been their increasing efforts to see stories like The Colored Museum and Pipeline brought to the stages of UA’s theatre department. The efforts of producing Blood at the Root are powerful because it the message from the students and by the students, and I hope they continue to use their student-led platform as a way to make sure that performances like these are used as a vehicle for change and not just entertainment.

Blood at the Root was performed at the Marian Gallaway Theatre, December 3 to 4, 2022. Directed by Trinity Ross, the cast included Jayln Crosby (Raylynn), Brianna Hammond (Toria), Raine Garlick (Asha), Marcus Johnson (Justin), Nathaniel Hudson (Colin/Principal V. O.), De’Andre (Chris Watts), Benjo Verge (District Attorney V.O.). The production stage manager was Kai Dixon. The lighting designer was Julia McDaniel. The sound designer was Benjo Verge. The dramaturg was Aleari Felton. The sound board operator was Gracie Price. The backstage crew was Erica Triplett and Susanna Latner.