The Susan Nomberg McCollough Fine Arts Initiative is a biennial event displaying work by alumni and students from the University of Alabama’s Department of Art and Art History. The featured pieces were selected from a pool of alumni and students, with each work having no given connection to the other save that they both attended or were part of the University. I was bewildered at how a show could provide any narrative or insight when the pieces were not selected around a specific theme. This immediate assumption did not account for other factors that went into the show’s production, however. The pieces were in fact curated with intention that created a narrative and perspective that the individual works could not provide on their own.

During my visit in late December, the exhibit flowed through the two front rooms in the Cultural Arts Center. One room exhibited pieces by alumni including sculpture, jewelry, photography, and painting. The second room contained work by students. After spending time in the gallery, I found that the structure of the show created an insightful experience for the viewer. I repeatedly saw the perception of identity being displayed through the concept of home, whether home as a place of origin, a person’s culture, or a physical house. The viewer was invited to see the transition from student perspective on home to alumni, including the lives, attachments, and identities formed by alumni separately from the student’s slow progress of creating and discovering their identity. The show considered the homes we physically build and the homes we build through relationship and connection.

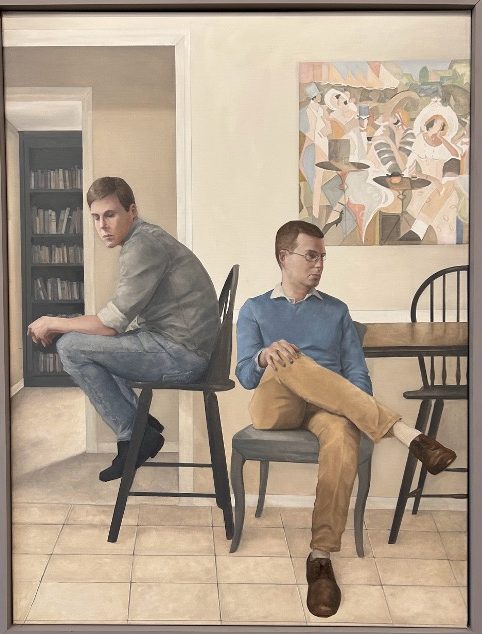

Upon turning into the student section of the gallery my eyes were drawn to the first painting on the right. Awarded Best in Show among the students, it stood out from the other pieces in its quality and depth. “Terms and Conditions” by Nathan Childers focuses on a home scene, where two men—a couple, presumably by the artist’s description—sit in a kitchen. They face separate ways but sit close together. The piece is soft as suggested by the pastel pinks and blues from a picture on the wall, a warm oak brown for the table, and beige tiles for the floor. The colors are enhanced through an understanding of depth and layering with a hallway in the background, and another painting hanging on the wall of the kitchen. The scene is comfortable. The couple sit close to one another and seem at ease in each other’s presence.

“Terms and Conditions” raises thoughts on the meaning of home, masculinity, and the queer community in the U.S. South. The setting is a key part to these perspectives. The scene here can be understood as the couple’s home, a place of safety and vulnerability. This is where the couple has created a shared identity, a life together. Their unique tastes, from the art piece on the wall to the chairs they sit on, are the physical attributes of a life they’ve made together. Along with this, their home is also a place for vulnerability. The viewer might wonder why they don’t look at each other. The tension seems so obvious you almost want to ask, but you know it’s not your place to; it would be an invasion of privacy. The cultural norm of avoiding, ignoring, and excluding the queer community in this part of the world is reflected as the viewer can only look, and never interact with the piece.

The piece is so subtle, the colors are soft, the subjects are simple, that it contrasts strongly with the subjects, two men. Culturally, vulnerability and softness are considered “feminine” attributes, yet here they are equated with masculine subjects, making these attributes also masculine. The piece confronts how identity is both exterior, and interior, affected by those around us, and our own selves.

I then came to “Port De Bras” by UA student Abigail Brewer. The painting was simply ethereal. It features a girl caught dancing, covered by a piece of tulle hanging from her hand, and glossed in resin. The glow of the resin creates movement, playing with the light shining on it. The term port de bras is used commonly in ballet. In French it means “carriage of the arms” but for most dancers it refers to a “series of movements made by passing the arm or arms through various positions.” The link to ballet surfaces crucial tensions for the work. Some see the art form as a continuation of a strict eurocentric ideology of idealized “feminine” form, while others as the most beautiful way to use the body. In using a balletic term, Brewer enhances the essence of gracefulness that dictated this piece. Ballet is not the only concept at play, however, but works in tandem with Chinese imagery and dance traditions. Juxtaposing the two traditions offered a beautiful example of a student discovering their voice, forms of expression, and identity, and creating something uniquely their own.

In thinking about home, the viewer can see that Brewer’s piece gives insight into creating one’s own home, simply by creating something she loves and connects with. Her description mentioned that she looks to “find new ways to create magical escapes for my viewer.” Today fantasy fiction, color-saturated social media, and film have become synonymous with escapism. Yet this physical piece, featuring both a fantasy-like illustration and a color-saturated canvas, asks viewers to engage in their physical habitat rather than escape behind a screen. Brewer expresses her own identity in this piece, creating imagery and colors that reflect her own imagination, joys, and fears.

The final piece that caught my attention was “Slug Invasion of the Chocolate Strawberry Paradox” by Libby Morris, another UA student. This title alone gives reason for having the work be a part of the show. Another home scene, the walls look like they are really oozing with chocolate and strawberries while the living room itself is plush and cozy. The piece is on stretched canvas, giving it a rough and warm essence.In fact, the home seems to be becoming part of the roughness, with sketches of white trees gently reaching into the picture. I liked how the piece turns the viewer back to ideas of home. How can home be a rough, chaotic place like this picture? Does this version of home negate other versions of self-discovery and comfort like in “Port de Bras”? I think that the growing pains of self-discovery and finding what home is, can be rough and chaotic. Perhaps home is the one place rough and chaotic is accepted and even needed.

The pieces by the students attempted to address many ideas of identity, home, sexuality, beauty, and imagination, while alumni seemed to focus on one idea: a house turning into nature or nature being a part of home.

Thinking of home—the connection between our built social realities, and the physical—I moved over to the alumni room. If there was a focal point to the show, “Tenant House I” by William Christenberry was it. The piece took up an entire wall. It focuses on a yellow beige house in the middle, surrounded by trees and grass, with another building in the distance behind it. The house is so similar in design to the surrounding nature that it almost looks as though it is part of it. The colors are bright and cool with soft light greens and yellows, blueish blacks, and purples. It made me breathe a little lighter. The brush strokes lean upwards, lifting the gaze and body away from the piece itself and more towards the light shining on it. The impressionistic landscape was overwhelming at first. Upon further viewing, however, it became enduring and peaceful. The work features an old and decrepit farmhouse, a house that is overtaken by nature. A comforting thought passed me, the idea that nature will live on when a human no longer inhabits the place. The physical essence of home is only temporary—a pit stop—yet for some plants and creatures, a place is their existence.

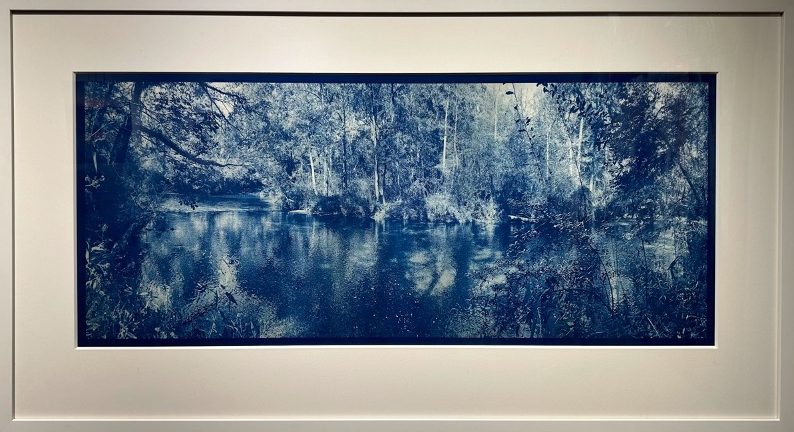

On the other corner of the wall hung “Cahaba Beach, River Bend” by Scott Stevens. The photograph was taken in a blue tone, giving it a coolness not regularly associated with river scenes. It created distance from me and the river and forced me to look at the river with new eyes. I liked how the photograph and the painting were placed close together so that home and place were implied as to be entwined. I find that place of origin can also be a unique aspect to our identity. When people ask, “where’s home?” they often want to know where you were born, or where you grew up. Place is so often connected to land. The wildlife and landscape that a person grew up around influences where they feel comfortable, or uncomfortable.

Home often feels like an elusive concept. Is a home four walls? Or is a home simply where you are most attached? In this show, home became a concept for something grander. “Terms and Conditions” considers how home can be a place of safety, where a life and identity can be built and accepted without the intrusion or judgement of others. “Port De Bras” gives the viewers insight into the artist’s own identity and unique home, as she creates beauty through blending the different parts of her life. “Slug Invasion of the Chocolate Strawberry Paradox” shows the artist’s view of home as rough and chaotic yet needed for the growing pains of self-discovery. “Tenant House I” gives the viewers an idea of how home can be part of a grander picture, as the farmhouse is blended into the landscape, home and identity is a small part of being human while “Cahaba Beach-River Bend” was an actual landscape, it still held onto the cultural importance land can have in identity. The houses, people, and places portrayed in student and alumni art captured the idea that home is created through place, relationship, and identity.

“The Susan Nomberg McCollough Fine Arts Initiative – A University of Alabama Biennial Event” exhibited at Dinah Washington Cultural Arts Center from October 6 through December 1, 2023. “Terms and Conditions,” Nathan Childers (spring 2024), oil on canvas, 48 x 40 inches; “Port De Bras,” Abigail Brewer (spring 2024), oil, resin, and fabric on wood panel, 30 x 40 inches; “Slug Invasion of the Chocolate Strawberry Paradox,” Libby Morris (spring 2025), acrylic on canvas; “Tenant House I,” William Christenberry 1960, oil on linen; “Cahaba Beach-River Bend,” Scott Stephens 2022, cyanotype.