Content warning: this article references race-based slavery, sexual assault, and violence.

“This is what it meant to be part of a slave-holding society”: it was this statement that punctuated the somber silence of my otherwise persistently boisterous history class. We’d been assigned Dr. Brenda E. Stevenson’s “What’s Love Got to Do with It?: Concubinage and Enslaved Women and Girls in the Antebellum South,” a recent study of racialized sexual violence inflicted upon Black, enslaved women in the American South. Rather than concentrating on the many names and life experiences charted in the article, I found myself unconsciously employing a sense of emotional detachment. By contrast, when our professor shared the entry on Luna in The University of Alabama’s digital exhibit, The History of Enslaved People at UA, 1828–1865, this detachment dissolved.

This digital exhibit, recently launched this past January, is one of several outcomes from 2004 and 2018 faculty resolutions “acknowledging and apologizing for the history of slavery at The University of Alabama.” This website, and the years of research and assessment that made it possible, is the first repository to document all the (currently known) enslaved people who labored and/or were affiliated with The University of Alabama before the American Civil War.

Telling the stories of enslaved individuals that labored on campus did not begin with this digital exhibit. Dr. Jenny Shaw, an Associate Professor of History, led the Task Force for Studying Race, Slavery, and Civil Rights, whose research, alongside Dr. Hilary Green’s development of the Hallowed Grounds tour, provide the foundation for the website. Research for the exhibition leveraged the brain trust of campus faculty alongside nationally-recognized scholars, including Drs. Alfred L. Brophy, Joshua Rothman, and Green. Over the course of the 2021–22 academic year, this research group conducted a systematic review of all university archives and materials that pertained to slavery in order to identify as many individuals as possible. The team then digitized and transcribed sources they collected to make them freely available to the public.

In their documentation of the development process, the research team emphasized that it “was important to recognize the shoulders the task force stands on” by speaking about past faculty members’ work that laid the foundation for this necessary project. The current collaboration across disciplines engaging undergraduates, graduates, and faculty continues in this tradition as evidenced during the launch event where, among other activities, a bookmark using an undergraduate’s design was distributed for free. The design featured a stylized graphic of the Little Round House, a prominent pre-Civil War structure in the center of campus, recreated in muted browns and whites on one side with some of the names of enslaved individuals that are written about on the website on the other. The team made special recognition of the graduate students’ “phenomenal work” and The University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections librarian Kate Matheny’s vital contributions.

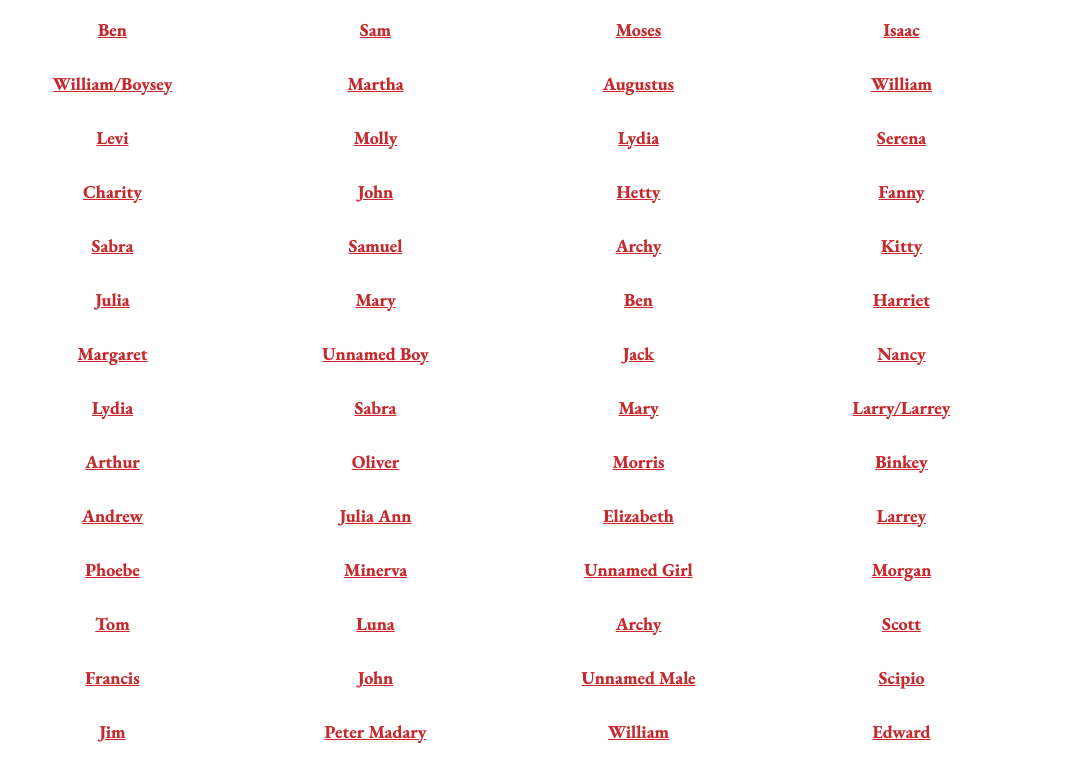

The website’s design is minimalistic with a red header and tabs, aligning with UA’s digital branding, that work to center the project’s aims rather than promote a particular education experience. Larger than the header running across the top of the page is the phrase, “Know Their Names,” a striking call to action that speaks to this project’s focus on telling people-first history. At the literal and figurative center of the design are fifteen names of enslaved people labored on and to make the UA campus. It is a small fraction of the over 150 individuals the project spotlights.

Luna’s particular entry begins simply by listing her name, sex (female), and freedom status (enslaved), as it would have been on a slave register or census. As I continued to work through the entry, to my surprise I began to recognize names. Her enslaver was Frederick Barnard, a professor whose name is currently inscribed over Oliver Barnard Hall on the central quadrangle by which I walk every day. I wondered what must it feel like for my fellow classmates who are the descendants of enslaved Americans to walk by and do their school work in buildings bearing the names of their ancestors’ enslavers. The final entry on the page came from the former University of Alabama President Basil Manly’s diary, in which he recounts how Morgan, an enslaved man, acted “as a Pimp” for “the younger Luna” who was “use[d] in great numbers, nightly” by white male students. Suddenly, the pre-class reading made sickening sense.

Despite the challenging facts the exhibition was bringing home for me, I continued to explore the resource outside of class. The History of Enslaved People at UA’s collaboration goes beyond UA. For example, the website’s “Further Reading” tab directs users to additional scholarship in the field of antebellum slavery in the US. This cross-institutional collaboration is facilitated by the fact that UA is a member of the Universities Studying Slavery consortium. In this consortium, over one hundred institutes of higher learning across six different countries share “best practices and guiding principles as they engage in truth-telling educational projects focused on human bondage and the legacies of racism in their histories.”

The project’s cross-institutional collaboration manifests in its use of the Linked Open Data (LOD) ontology developed by Michigan State University, Georgetown University, and University of Virginia in their collaborative On These Grounds project, a precursor to what became the consortium. LOD allows users to track linked vocabularies to sort through large amounts of data and so better explore trends in the experiences of enslaved individuals on university campuses. This ontology aims to describe the “lived experiences of those enslaved individuals who labored in bondage in higher education institutions” that are often obscured since many records from the period were created by white enslavers that did not recognize the humanity of the people they enslaved. The LOD ontology gives clear definitions for words like “enslaved,” creates categories for these words like “resistance, labor, and violence,” and allow researchers to search for categories. Establishing linguistic best practices helped UA’s digital exhibit to avoid pitfalls of past historical scholarship on slavery, such as inadvertently mimicking enslaver language and vocabulary like calling enslaved individuals “servants.”

The ethos behind the ontology is best seen in the “Their Lives” page. On this page, users can read entries which have compiled archival information about all the enslaved individuals currently known to have labored at UA. I found this part of the website most impactful. The horror I felt from Luna’s story was both heightened and made constructive as I read entry after entry. Jerry was stabbed with a fork by a student. Former University President Manly and students whipped Sam. Phoebe delivered her child, Minerva (aptly named after the Roman goddess of justice), who was then later referred to as “it” by an enslaver account. By reading these human-centered entries, I was able to see clearly how The University of Alabama could “not do business for a single day” without the violence and theft of slavery. There were varying amounts of information available about each person from “Their Lives,” so the “Overview” tab importantly recognizes any unnamed enslaved person whose stolen labor, knowledge and skills contributed to UA. The page also importantly remembers the lives of enslaved people beyond their freedom status, highlighting their resilience, resistance, and agency.

This user-friendly design, with easily navigable, digestible, and interactive elements, helped me interact with the stories being told in a variety of other ways, too. The “Timeline” entry chronicles events in the University’s history from before and immediately following Emancipation. For example, the website’s “Database” allows visitors to examine any one of the over two hundred items and archival documents currently on the website. While I conducted simple searches based on the materials’ creation date, an advanced search allows for far greater specificity. The “Timeline” entry allows users to scroll through some flashpoint moments using a personal device’s touchscreen or arrows. As I tabbed through and viewed the titles, descriptions, and photos, events included national news and UA events like “52 students (all white boys) matriculat[ing],” but still centered around the lives of enslaved individuals at UA. Having engaging and diverse ways to view information ensures the exhibit meets users where they are at and whatever their needs may be.

It is through these design and infrastructure choices that the exhibit is able to share and digitize UA’s historical resources to those with a range of access needs. The website adheres to UA’s required ADA design guidelines, which utilize high color contrast and alt text on photographs. Using these requirements as a springboard, the website’s cognizance of its users’ emotional and linguistic capacities goes a step beyond what is required of it. Including content warnings throughout the site prepares visitors to learn about stark realities of how enslaved people were treated at this institution. Sentences are concise, laying bare the atrocities were committed to help “the University of Alabama flourish in its first decades.” “Enslaved people were beaten and whipped by students and faculty for the smallest perceived indiscretion or simply for entertainment”: it is a sentence that does not have difficult syntax or complex verbs. It is this simplicity that illustrates slavery’s violence and brutality with language that users can easily grasp.

Based on my experience, I can see how the website’s interactive elements, accessibility, and clear prose makes it intelligible to a wide range of users. The History of Enslaved People at UA claims the information that it presents is not perfect, however, but that the exhibit is “an attempt.” The website’s homepage takes the time to explain the purpose behind each of the tabs, and frequently uses qualifying phrases like “so far” or “some” to describe the information within. These caveats use personal pronouns, taking effective responsibility for any oversights within the project. By revealing potential shortcomings of the materials presented—not being comprehensive, potentially having errors in transcription or analysis, and the materials used to create it coming from white enslavers or from state institutions supported by slavery—the Task Force reveals both earnest humility and a commitment to further research.

That this is an ongoing project is an authentic stance; new research is being conducted, for example, as part of undergraduate classes. One option for students to complete their senior capstone project for a degree in History is the course, “Slavery at The University of Alabama,” in which they are using source material from the website to write biographies centered around an enslaved individual from the “Their Names” page. The Task Force has also been asked to continue their work as part of a second phase to the project exploring the Jim Crow era post-1865, as well as the Civil Rights and Black Power movements.

As Dr. Shaw pointed out when I spoke to her in an interview for Ripple, The University of Alabama publicly acknowledging and taking responsibility for how enslaved individuals’ labor and lives built this institution sends a powerful message to the communities around it. (According to the most recent census, over thirty percent of Tuscaloosa county residents—where the University is based—identify as Black or African American, and over forty percent of Jefferson county residents, which includes Birmingham, the largest city in the state. Only eleven percent of students currently enrolled identify in this way.) That message and the communities the University is responsible to extends far beyond the physical campus here in Tuscaloosa. As the state’s flagship institution, anywhere the University’s vast out-of-state population calls home has the potential to be impacted by this exhibit’s careful construction of human-centered history. The History of Enslaved People at UA preserves stories of people like Julia Ann, Larrey, Thornton, Lewis, Dan, Berry, Monroe, Green, and Lydia. Knowing their names is only the first step in prioritizing their memory.

The History of Enslaved People at UA, 1828–1865 (studyingslavery.ua.edu) is hosted by eTech and The University of Alabama. Katharine Buckley, Briana Weaver, Valero West, and Jenny Shaw were members of the Research Group on the Task Force for Studying Race, Slavery, and Civil Rights for UA that developed this exhibition, with additional support from Alfred L. Brophy, Hilary N. Green, Joshua Rothman, and Kate Matheny. The digital infrastructure uses LOD developed by Sharon Leon and the On These Grounds: Slavery and the University team. Special thanks to Dr. Shaw for her interview and insights.